Moments of Democratic Opportunity in 2026

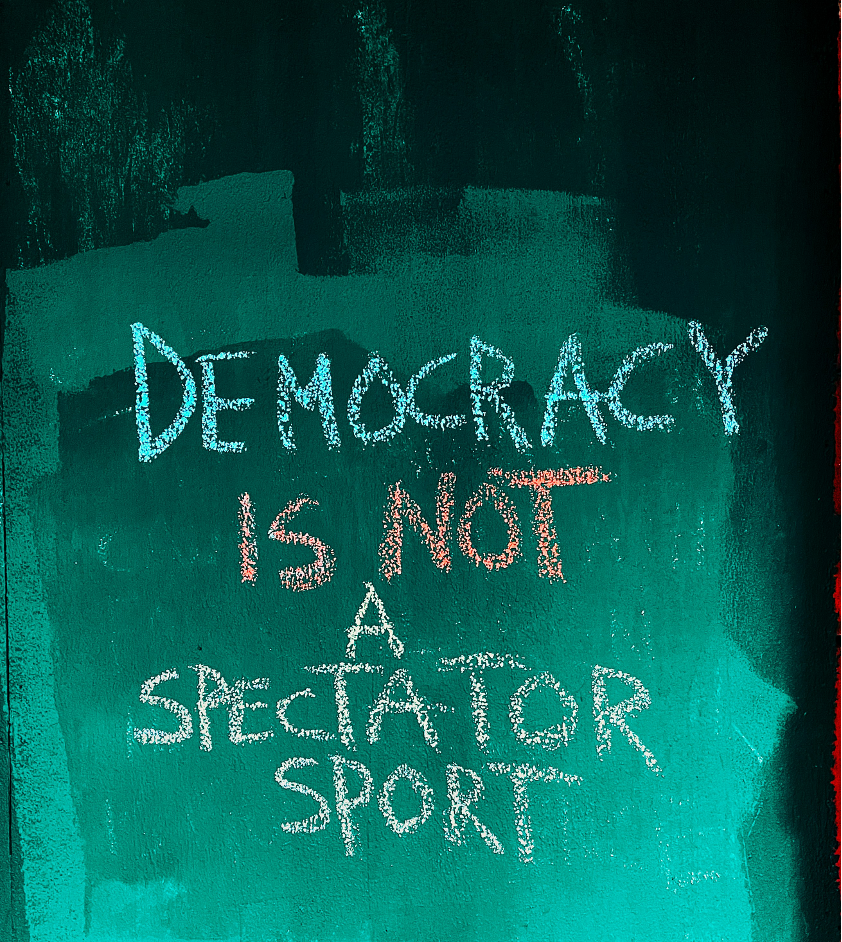

If 2024–25 felt like the era of election overload globally, 2026 is a time to pay attention to something subtler: the streets, institutions, rules, and city halls that help decide whether the next decade’s elections provide genuine choices and function as the mechanisms of accountability they are supposed to be. Across every region, 2026 will present several kinds of “democratic moments”: midterm and parliamentary elections, referendums on new constitutions, first competitive contests after authoritarian rule, and early implementation of major governance reforms.

Hence, 2026 is more than a crowded election calendar and set of “elections to watch”; it should be seen as a year of diverse democratic opportunities that require attention, amplification, and engagement. This article highlights key opportunities and what to watch for—but more importantly, provides lessons and insights on how these opportunities may be instrumentalized and not thwarted.

National elections as democratic turning points

Several headline contests this year are important to watch as genuine forks in the road for democratic trajectories, not just changes of government. They crystallize deeper struggles over executive dominance, corruption, and social contracts.

In Bangladesh, the first general election since the 2024 student-led uprising that forced Sheikh Hasina from power will test whether the “July Charter” reforms—intended to curb prime-ministerial dominance, strengthen courts, and depoliticize security forces—can be translated from protest manifesto into a functioning constitutional order. Bangladesh will signal to protest movements in other countries whether negotiated reforms can tame entrenched ruling parties or simply launder their rule.

In Nepal, the 2025 Generation‑Z–led protests toppled the government and produced an interim administration charged with organizing new elections. Youth activists leveraged digital platforms to coordinate mass demonstrations and contest entrenched patronage politics, and the March 2026 national elections are now framed as a decisive test of whether this insurgent, youth‑driven push for accountability can be translated into youth political engagement and lasting institutional reforms.

In Colombia and Peru, 2026 presidential and general elections come amid fatigue with turbulence and scandal, and they will determine whether voters double down on anti-corruption and social-justice agendas or swing toward law-and-order populists. They also take place within a volatile regional context following the intervention of the United States in Venezuela. Meanwhile, Brazil’s 2026 presidential contest will follow a period of polarized politics and institutional strain, and will help decide whether the country consolidates recent democratic stabilization or re-opens the door for anti-system forces to harness public anger over inequality and crime.

In Hungary, the April 2026 election will test whether a newly energized opposition led by Péter Magyar’s Tisza Party can overcome an electoral system systematically engineered to favor Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz. A competitive race here would be a stress test of whether elections can still correct course inside one of the EU’s most entrenched illiberal democracies.

Israel is expected to head to the polls by late 2026, in what could become a de facto referendum on Benjamin Netanyahu’s leadership and the handling of corruption cases and regional security crises.

Testing of new rules and systems

2026 is also a year when fresh institutional designs are being tried in real contests, with outcomes that echo well beyond a specific 2026 election to whether new rules make future elections fairer or more tightly controlled.

In Benin, contentious constitutional reforms have sparked renewed debate (and a failed coup) before the 2026 legislative and presidential elections, with critics arguing that changes to term limits, candidate requirements, and party rules have narrowed competition. How the electoral commission handles candidate registration, ensures free and fair competition during the campaign, and dispute resolution for the upcoming presidential elections will determine whether Benin can reclaim its earlier reputation as a democratic pacesetter or drift toward competitive authoritarianism.

Armenia heads toward its 2026 parliamentary elections with the government openly preparing a “fourth republic” constitutional project to follow the vote, designed to reset state identity and borders after the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis. A promised referendum after elections will be a high-stakes test of whether constitutional redesign can stabilize a wounded democracy or instead concentrate power in the hands of a shaken but still dominant leadership.

In the United States, 2026 is a pivotal year for electoral-system reform at the state level, with ballot measures and legislative proposals moving to replace closed partisan primaries, adopt top-two or ranked-choice systems, experiment with forms of proportional representation in local and sometimes statewide elections, tighten voter registration requirements, and encourage mid-decade partisan redistricting. Some changes could gradually make one of the world’s most rigid electoral systems more open and representative, while others may restrict voter access and deepen political entrenchment.

Somalia’s planned 2026 parliamentary elections, framed as a step toward more broadly based “enhanced indirect” voting, aim to dilute elite manipulation inside the long-criticized clan-based model by tightening rules on who can stand and how delegates are chosen. Whether the new safeguards are enforced is the difference between a transition toward more representative politics and a rebranding of old bargains.

In the Pacific Islands, the democratic stakes in 2026 lie less in headline elections than in rules, institutions, and political arrangements that shape whether elections remain meaningful. Small electorates, weak party systems, and heavy reliance on constituency-level politics mean that modest legal or procedural changes can have outsized effects on political competition. These dynamics are further shaped by large diaspora communities. Decisions about overseas voting, voter registration, and representation therefore carry unusual weight.

In Solomon Islands, post-2024 debates over anti-defection rules, constituency development funds, and parliamentary oversight will determine whether elections continue to hold leaders accountable to voters and parliament or gradually entrench governing coalitions. Papua New Guinea offers a parallel test: reforms designed to stabilize governments may reduce chronic instability, but risk weakening legislative scrutiny in a highly personalized political system. Meanwhile, in climate-vulnerable states such as Kiribati and Tuvalu, decisions on overseas voting, constituency boundaries, and public finance will shape whether future elections remain inclusive as displacement grows. Across the region, including in Vanuatu and Samoa, the interaction between elected institutions and customary governance remains central to democratic legitimacy. The Pacific highlights a broader lesson for 2026: institutional design - not election day alone - often determines whether democracy endures or quietly erodes.

“Will they happen?” elections

Some of the most consequential electoral moments to watch in 2026 may not be moments at all. These represent potential democracy opportunities and conflict-risk indicators at the same time.

Libya: elections vs endless transition. Libya’s High National Elections Commission has declared itself technically ready for long-delayed presidential and parliamentary polls, pointing to completed technical preparations and a track record of recent municipal contests. Yet rival authorities in Tripoli and the east remain locked in disputes over electoral laws, security arrangements, and the interim executive, with the parliament speaker and the High Council of State accusing each other—and the election authority—of blocking the process. Whether Libyans actually vote in 2026 depends on a fragile elite bargain that could still collapse into yet another extension of the transition.

South Sudan: vote first, fix the deal later? South Sudan’s leaders have amended the 2018 peace agreement, allowing to push elections to late 2026 while sidestepping some prior benchmarks on a permanent constitution and security arrangements, arguing that a vote is needed to end the “transition without end.” Opposition parties and civil-society groups warn that moving ahead without robust security reform, a census, and broad consensus on rules risks turning elections into a winner-take-all contest that reignites conflict rather than legitimizes power-sharing.

Ukraine: democracy at war. Ukraine’s regular electoral calendar collides with the necessity of martial law, which currently suspends national voting while the country is engaged in full-scale war. Depending on developments in peace negotiations, Ukrainian leaders and partners face hard questions about whether and how to organize credible elections with occupied territory, millions of displaced citizens, and unequal security conditions, raising profound issues about representation, the franchise, and constitutional continuity in wartime.

Palestine: elections as permanent “future.” Palestinian presidential and legislative elections have been repeatedly promised and postponed, and 2026 opens with deep uncertainty following the devastation in Gaza and new interim governance schemes under discussion. Plans for stabilization forces and administrative arrangements reference future national elections, but there is still no clear, agreed path or security framework that would allow Palestinians in Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem to vote safely and freely. The danger is that “upcoming elections” remain a diplomatic talking point rather than a real horizon of democratic choice, or that national elections become a geopolitical bargaining chip at the expense of meaningful investment in locally-led, subnational democratic development.

Local democracy: subnational reforms and local contests

If national elections are the stage for headline struggles, subnational reforms and contests in 2026 are where democratic practice is being quietly redesigned. Local changes are showing how democracy can be strengthened from the ground up, and are also often a safeguard against conflict and breakdown of democracy in situations of fragile statehood.

Across the United States, cities and states, 2026 will deepen experiments with ranked-choice voting (RCV) and various forms of proportional representation, reforms aimed at rewarding coalition-building, broadening representation, and reducing zero-sum polarization. Washington, D.C., for example, is moving toward implementing city-wide RCV after a strong referendum result and council approval, putting the nation’s capital among a growing group of jurisdictions that let voters rank candidates instead of choosing just one.

In Rotterdam, the Netherlands, the “Wijk aan Zet” model has created elected neighborhood councils across the city, open to independents and to 16- and 17-year-olds, and 2026 will see these bodies continue to embed a culture of hyper-local representation and youth participation in decision-making. The Czech city of Brno is continuing its “Dáme na vás” participatory budgeting program—now several years in—that lets residents propose and vote directly on local spending priorities, a model inspiring similar efforts elsewhere in the country.

In 2026, several African countries are testing new political and institutional models at the grassroots. In South Africa, municipal polls will take place under a maturing coalition system, where parties are piloting pre‑election pacts, clearer coalition agreements, and highly targeted ward campaigns to stabilise fragile metros. Benin’s combined legislative and municipal elections operate under stricter thresholds and coalition rules that push parties into larger blocs, offering a laboratory for how electoral engineering reshapes local party systems. In Ghana and Zambia, reforms around gender equity, youth leadership and party finance are being tested in local arenas, making council races a key indicator of whether new laws actually translate into more inclusive representation and fairer competition on the ground.

In Fiji, attention in 2026 will focus on the resilience of constitutional and institutional safeguards around the courts and electoral system, making the country an important test case for democratic consolidation in the Pacific. Long-delayed local government elections remain a critical missing layer of accountability. Whether Fiji restores elected local councils or continues to rely on appointed administrators will shape how deeply democratic practice extends beyond the national level.

External leverage and democratic consent

A growing democratic challenge in 2026 - visible in the Pacific and relevant elsewhere - is how small, aid-dependent states maintain democratic consent when major policy choices are shaped through unequal external relationships.

Palau illustrates this tension. Under a memorandum of understanding with Washington, the government has agreed to accept up to 75 migrants transferred from the United States in return for additional aid. In a country of roughly 18,000 people, this represents about 0.4% of the total population, making the agreement significant in social, administrative, and political terms despite its modest absolute scale. The democratic question is not cooperation itself, but whether commitments with lasting implications for migration policy, public services, and sovereignty are subject to meaningful parliamentary scrutiny, transparency, and public debate. Comparable questions arise in other regions where governments negotiate externally linked agreements on migration management, security cooperation, or financial support. In such cases, democratic accountability depends less on elections alone than on whether representative institutions can authorize, oversee, and contest decisions that reshape domestic governance.

What to monitor and support in 2026:

Taken together, these potential democratic opportunities highlight several lessons about how democratic trajectories may be shaped in 2026 and beyond.

Treat rules and institutions as the real battleground.

Focusing attention and support on how these institutions - public officials, judges, magistrates, media and democratic actors are designed, funded, and protected is at least as important as tracking polling numbers. It is rules and institutions that determine whether elections and democratic processes are inclusive and credible. As such, it is important to understand and monitor hybrid threats to these institutions and use a full suite of tools to counter them (such as digital monitoring and an accountable sanctions regime).

Invest in local democracy, not only national drama.

Subnational reforms show that democratic innovation often starts where citizens experience government most directly. Backing local election administration, participatory mechanisms, and accountable mayors can pilot innovative ideas, build habits of trust and inclusion that national politics later inherits. The same is true for conflict transformation: national governments in many fragile states are not capable of exercising control over non-state disruptors, especially where they are geographically dispersed. Rather, emphasis should be on incremental transitions that leverage and build on existing pockets of cohesion and effective authority at the local level.

Consider the impact of dramatically reduced development assistance for elections and democracy.

Year‑round investments in election management bodies, local media, civic education, and accountability mechanisms are still crucial, even if at smaller scale, and should be prioritized over resource-intensive international missions. This requires better partnerships, more nimble and sharp interventions, and deliberately shifting power, resources, and agenda‑setting to domestic actors who can sustain democratic practices.

Guard the “will they happen?” cases as priority tests for the intersection of peace processes and electoral integrity.

In Libya, South Sudan, Ukraine, and Palestine, the core question is whether meaningful elections can and should occur at all under current security and political conditions. Diplomatic pressure, peace-process and electoral system design, and international support should be calibrated to make those elections real—not just scheduled dates—but also safe, inclusive, and anchored in credible institutions.

Monitor the intersection of external government agreements and internal accountability mechanisms

In small, aid-dependent states, major policy choices tied to external agreements can fundamentally reshape a country, and should be grounded in democratic consent.